BACCA workshop with Michael Klein

This summer I have been very busy taking a Maya modeling class while I am also working on a personal project. Although most of the work I've been doing involves staring into my computer screen for most of the day, when I heard artist Michael Klein would be teaching a floral still life workshop at the Bay Area Classical Artist Atelier, otherwise known as BACCA, I jumped at the chance.

Here are just a few examples of Michael Klein's work, focusing on his florals. His work encompasses figures, still lives, and semi-narrative pieces, all done in a painting manner that brings the spirit of the subject to life with energetic, yet carefully planned brushwork. Much more of Klein's work can be seen on his website:

I love the textures and depth that he paints in his floral arrangements. They remind me a little of Fantin Latour florals while still being all his own.

Michael Klein's progress shot from his blog on his website. GORGEOUS!

********************************************************************

BACCA

********************************************************************

Materials

Old Holland Viridian Green Deep

Michael Harding Raw Sienna

W and N Yellow Ochre Pale

W and N Cadmium Yellow Pale

Rublev Lead White no. 2

OH Cad. Orange

W and N Burnt Sienna

W and N Perm. Alizarin Crimson

OH Quincinadrone Magenta

W and N Cobalt Violet

W and N Cobalt Blue

OH Ultramarine Blue

OH Ivory Black

OH Raw Umber

OH Burnt Umber

Mediums used were simply Gamsol for cleaning brushes, which he uses mostly on the first day to thin down the paint a little if it's too thick or sticky. After day one, he uses a widely known mixture known as "fat medium", equal parts linseed oil plus damar varnish. In later stages of his paintings, he makes use of Rublev Oleogel to thicken up paint strokes and add texture. Paint rags were Viva paper towels.

I did not have Oleogel for the class, so Michael gave me a tiny smidgen to test out. The gel is used for glazing, but also for adding body and flow to the oil paint on top layers. It is truly amazing stuff. I ordered a big vat of it along with the lead white. Michael noted that with Lead White he will sometimes mix it with a few drops of walnut oil to loosen up the stiff mixture. (He also uses stack white from Rublev to create texture, although he wasn't using it in this workshop.)

Michael's custom brush set right under that tube of paint.

*****************************************************************

Each of the four days of Michael Klein's workshop, he worked on a painting demo. He typically spends about 3-4 days working on a floral still life.

Mixed in with his natural flowers were two artificial flowers, which he doesn't like to use but did for this class. He noted that when flower companies make good quality artificial flowers, they mimic natural color patterns of the flower, like spray painting the joints of the stems and leaves with a little brownish overlay instead of one uniform green and will also boost saturation of petals. When using artificial flowers, you will need to understand the methods that manufacturers use to make their flowers appear real and compensate by using your observation and knowledge of real flowers. However, use real flowers whenever possible.

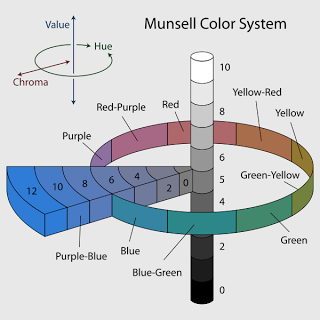

As for color mixing in general, he explained that he doesn't like to overmix his colors on the palette, but instead "loosely" mixes, keeping a bit of each original color separate, so that when the colors move on to the brush and then the painting, a light effect mixes them in our eyes, producing a color vibration. This is a technique I've seen before and used myself, especially with pastel paintings, and also have read about. Golden aged Illustrator Haddon Sundblom's painting method included using two pure colors on one brush to create a mixture directly on the canvas. I'm not sure if this method is an innovation by the Impressionists, but the idea of vibrating color via broken color and paint layers feels impressionist to me.

Also, regarding color mixing on the palette, Michael encouraged everyone to create a "puddle of color" that is essentially a color portrait of the thing you are painting, otherwise you will end up with a lot of muddled color. My own tendency to dance around the palette with all sorts of mixtures usually leads to confusion at times, which I need to work on correcting. He does not create "strings" of color on the palette, instead he creates the middle hue, shadow and light hues all in one puddle.

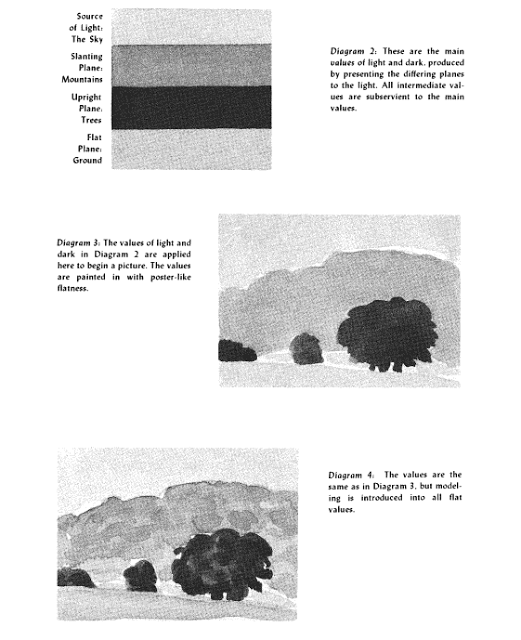

During his demo, he spoke a bit about using a combo of observation vs. knowledge of form. He explained that Jacob Collins emphasized a thorough understanding of form and how light moves across it, and it was when he finally understood what that meant, that he finally made some breakthroughs in his work. He went on to explain that after painting the initial gesture on the first day, he will start thinking about what he knows about how light reacts on the surface of particular forms. Often, he will not look at the still life but instead focus on the object being painted, paying attention to the direction of the light source and modeling the form so that it reads clearly while still maintaining the beauty of the still life.

This becomes particularly necessary when painting subjects like flowers, which change each day. When asked about his atelier training compared to how he paints now, he explained that in his current work, he is now concerned with evoking a mood or a feeling rather than rendering every bit of the subject in front of him, trying to find that balance between the truthful statement vs. gesture.

For form painting demos, Michael recommended the excellent form painting lessons by fellow Grand Central graduate, Scott Waddell. I've seen all of Scott's videos and they are indeed incredibly useful.

My final painting, which I've cropped to make a more attractive composition.

On the fourth and final day, Michael helped me at the end make some value relationship adjustments and talked with me about editing to the highlight, which did not serve the overall painting as it was too eye catching and distracted from the main subject. His emphasis throughout the workshop was always on the final, poetic statement rather than a 1:1 rendering of the subject, which I agree with wholeheartedly.

Michael Klein's finished four day demo.

During his demo on the fourth day, he spent some time working again on the main white rose, making shifts to it because it had opened more fully than it was a few days earlier. Rather than repainting it entirely or making too many drawing adjustments, he simply added to it, explaining that he liked that the new additions added more variety to the painting.

*****************************************************************

Is it Alla Prima?

I think over the years that the term Alla Prima has become overused and misunderstood. Alla Prima is strictly a one session painting. That session might last a full 12 hour day, sure, but it is always one session, wet into wet. This came up because I think, generally speaking, people tend to assume that any painting that has a looseness to it is an Alla Prima statement. I asked Michael if his paintings are not AP, what are they? His answer was simple, they are just paintings!

On a personal note, when I was first introduced to oil painting as an 18 year old art student at the American Academy of Art in Chicago and then at the Palette and Chisel where Richard Schmid and many other amazing artists were painting, I fell in love with what the medium could achieve and the promise of what I might be able to as well. I had never seen paint become so intriguing; sketchy, energetic brushwork that came together in harmony to represent everyday things like portraits and figures, still life, and animals with rich color and layers of texture. That is where I first heard the term Alla Prima, the painting approach that Richard Schmid popularized throughout the 80's and 90's and especially with the release of his book, Alla Prima.

1993, I think. I believe this was a four hour demo. I mainly remember being so stunned at how quickly he was able get down rich color juxtaposed against greys in the white objects - and especially how loose and sketchy it all was.

Of all those years, this unfortunately blurry photo along with the one above are all I took of the actual man. The majority of my photos taken were of actual works hanging on the walls in revolving shows, auctions or works in progress. I'm still kicking myself for taking these blurry photos!

As much as I love a good Alla Prima sketch, my question has always been the same, how can I maintain the look of an Alla Prima sketch but work on it for multiple days without losing that fresh brushwork? Often, when I worked on a painting more than one day, many of the problems I encountered in this workshop were similar - sinking in, dry cracking paint, or thick paint that just looked dull and lifeless, overworked, over rendered, boring. I've always admired painters that are able to maintain a fresh feel in their longer pieces, giving the impression that the work was painted quickly and effortlessly. It was a pleasure to finally meet Michael Klein and get to chat with him about various ways to strategize and plan a painting to create a mood, a visual poetry, throughout a longer, more elaborate work. What a great experience, one that I will keep close throughout my new paintings.

Note: My next several updates will be a switch back to digital work for a personal project I am working on. Entirely different, and yet so many of the core concepts overlap one another.

Thanks for reading!